SELOKOLELA, Botswana/UNITED NATIONS, New York – “Menstruation is still considered a secret that is hardly discussed,” Ogaufi Moisakamo, in Botswana, told UNFPA. “When I got my first period, I was also ashamed of informing my mother. And when I finally told her, she only warned me against playing with boys as it would ‘get me pregnant’.”

This experience is all too common, UNFPA has found. It is often the subject of whispers and embarrassment, not only in families and schools, but also in the halls of power: Not so long ago, menstruation was regarded as so taboo it went almost entirely unmentioned in the world of diplomacy and development.

Even in the last 30 years, as international development and humanitarian experts began to focus on water, sanitation and hygiene as essential for human rights and dignity – work that necessarily includes indelicate topics like toilets, sewage and waste disposal – menstruation was generally absent from the conversation.

But all that is changing.

The last decade has seen a major shift in how advocates talk about menstruation. They are refusing to treat the issue with timidity or shame. They are highlighting that menstruation is not only an issue of health, hygiene and dignity, but also as a matter of gender equality and human rights. They are unapologetically calling for all menstruating adolescents and adults to be able to access school and employment and to access safe, affordable and acceptable menstrual supplies.

In 2014, on 28 May, the international community marked the first-ever Menstrual Hygiene Day, and the observance has only grown over time. This year, UNFPA is highlighting the progress that has been made, the taboos shattered, awareness raised and the efforts committed to meeting the needs and securing the health, dignity and rights of those who menstruate around the world.

1. Menstruation is increasingly recognized as being a human rights issue.

Recent years have seen the issue of menstruation increasingly addressed at the United Nations. In December 2019, the UN General Assembly expressly recognized the neglect of menstrual hygiene management as an issue in schools, workplaces, health centres and public facilities, with negative effects on gender equality and human rights (including the right to education and the right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health).

More recently, in July of last year, the first-ever resolution on the issue of “Menstrual Hygiene Management, Human Rights and Gender Equality” was adopted – by consensus – by a United Nations intergovernmental body, the Human Rights Council. This resolution highlights the issues of shame, taboo, stigma, misconceptions, myths and exclusion that often result from insufficient information, health services, menstrual supplies and sanitation infrastructure, and calls for the Human Rights Council to take action.

A panel to take up the issue will be convened in June.

2. Policymakers are increasingly taking action on the domestic level.

At the Upper Primary Government Girls School in Naya Gaon, in Rajasthan, India, girls have to fill and carry buckets of water to use the toilet because there is no running water. Inadequate sanitation facilities can affect girls’ school attendance. Image from 2018. © UNFPA India

Ten years ago, there was relatively little public awareness about the public health, economic, social and human rights consequences of menstruation stigma. But since 2014, the term “period poverty” – the increased economic vulnerability that can stem from the cost of menstrual supplies, pain management and other menstruation-related issues – has gained traction in the public consciousness.

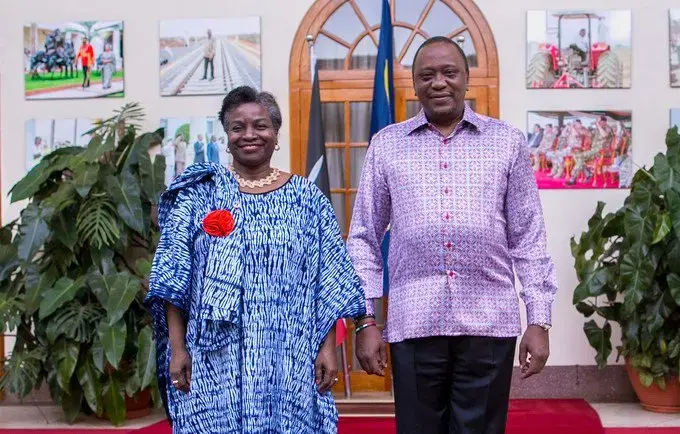

Today, policymakers are unabashedly addressing these issues in ministries, parliaments and courtrooms. India, Kenya and South Africa, for example, have adopted policies and strategies to ensure that adolescents learn about menstruation and menstrual hygiene, to de-stigmatize the issue and to support access to quality menstrual supplies. Australia, Canada, Germany, India, Ireland, Kenya and others have reduced or eliminated taxation of menstrual products. And some countries are even instituting paid menstrual leave for those experiencing painful or disabling periods.

3. Quality standards for menstrual products are being adopted around the world.

The taboo and silence surrounding menstruation contributes to poor knowledge about the role of poor quality menstrual supplies and practices and vulnerability to urogenital infections. But the issue is not only the lack of quality research, it is also inconsistency in product standards.

In recent years, governments, organizations and supplies experts have begun to press for improved quality standards. For example, groups like the Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition and others have developed quality specifications for disposable menstrual pads, reusable menstrual pads, menstrual cups and tampons.

4. There is growing awareness that the needs of menstruating people will not be fully met by products or supplies. It is just as critical to address harmful social norms, eradicate stigmas and provide comprehensive sexuality education.

Products are simply not enough, advocates and researchers have found. In some settings, for example, providing free menstrual supplies does not improve access because community members are too uncomfortable to even talk about menstruation in the first place.

When Kenathata Moisakamo – the little sister of Ogaufi in Botswana – started menstruating, she kept it a secret. Fearful of being ridiculed, she skipped school. Fortunately Ogaufi knew from her own experience what was going on, and she sat her little sister down to explain that menstruation is nothing to be ashamed of.

Kenathata Moisakamo learned about menstruation from her sister and from a UNFPA-supported comprehensive sexuality education programme. © UNFPA Botswana

Then Kenathata began to receive comprehensive sexuality education through a UNFPA youth programme. The lessons explained how her body works, and also taught her to speak about menstruation and other reproductive health issues without fear or embarrassment.

Dispelling misinformation and eliminating shame are critical, not only to improving menstrual health but also to empowering young people to advocate for themselves in all areas of sexual and reproductive health and rights. “Now that I understand…contraceptives, menstruation and teenage pregnancy, I proudly share this knowledge with my peers and cousins who are not part of the programme,” Kenathata told UNFPA.

UNFPA is working with organizations and partners around the world to improve stigma-free information about sexual and reproductive health, including menstruation, and to empower young people to stand up for their health and rights.

5. Young people are taking the lead.

Young advocates are driving much of this change. “During youth consultations, I noticed that young people are ready to break the taboo around menstruation,” said Laura Bas, the new Youth Ambassador for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights, Gender Equality, and Bodily Autonomy in the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

In her work, she speaks with youth leaders from around the world. “Young people are full of creative ideas to normalize talking about menstruation. Young girls from South Sudan told me that they wanted to create buddy systems at high schools, where older girls teach younger girls everything they need to know about menstruation,” Ms. Bas said.

Other young people, such as Viwe Goboza, in South Africa, is taking on both the stigmatized issue of menstruation as well as the neglected needs of LGBTQIA+ people, highlighting the menstrual needs of transgender and non-binary individuals.

The African Youth and Adolescent Network (AfriYAN) is launching a number of youth-led efforts to improve information about menstruation, call for better water and sanitation facilities in schools, and integrate menstrual health and hygiene into crisis planning. And they are not stopping there.

“As young people, we still commit to pushing more, so that more young girls can have access [to quality facilities and products] and understand their menstrual health… so that we can have the Africa that we want,” Lorence Kabasele, President of AfriYAN, said.